Induction Heating

After BEPA

NOTE: The use of exact dates in this chapter is to allow any reader that can use my document files to follow the story in more detail.

On October 11th 1985 I showed my two year work permit at Heathrow Airport that allowed me to remain and work in the U.K. Immigrations officers (perhaps MI5) took us into separate rooms for an interview. They asked me in passing questions about carbon-carbon. Vera's visa stamp gave her a temporary right to remain with me in the UK as my dependant. We were following all the rules to allow her to be become a "Nationalized citizen." My accountant could now file my British income tax forms. It had been my plan to sell our house in Motherwell before the end of 1985 and the accountant was waiting for that event. Rule #1 and rule#2 of the attached document covers the tax rules for the expatriates.

http://www.ioa.com/~zero/530-Tax.html

My next task was to fire Soderstrom because Calcarb or Consarc did not want his services. It was my feeling he would remain on the Russian project with Dick, who would surely pick up a contract in his own company's name. He asked my advice, but I could only tell him to seek legal advice. As it turned out, the CIA called him claiming to be the FBI from the American Embassy in London. The telephone message was from a man without a name. He told him that while he had broken no law to date, that if he returned to Moscow they would find a way in which he had broken the law. He was fired effective from 15 October 1985.

I called the Duty Officer (CIA) at the American Embassy to get the same warning. They refused to admit that Soderstrom had been given a warning.

We continued to have problems sorting out what we could ship to the Russians in place of the useless cold bottoms. The items that were denied included a simple battery operated tow truck, an electrical cable, electronic parts, and some parts that had no connection with the project. The letter from DTI denying these items informed us that laws were being changed and they would be permitted in ten days time when the new CoCom regulations were released.

The following letter from the DTI confirmed the stupidity of governments. The British had now approved everything useful to the customer. Their refusal to approve the cold bottoms remaining in our inventory forced us to offer the Soviet buyer additional items in the same dollar amount. On the positive side, we were able to continue getting rid of our scrap pile of carbon.

From: Department of Trade

18 October 1985

Dear Mr. Wilson

Further to my letter of 3 September 1985, my technical colleagues have now studied the additional information supplied by your company on item 1105 (water cooled flexible power leads) and item 1110 (battery electric tow tractor). As a result of these further considerations I can confirm that item 1105 (water cooled flexible power leads) and 1110 (battery electric tow tractor) do not require an export license.

The Department has also assessed your export license application for two Body Bottoms (Base) which was handed to Mr. D. Hall by Mr. W. Cooke on 3 October 1985. In the light of this consideration an export license is denied.

Yours sincerely

Hall

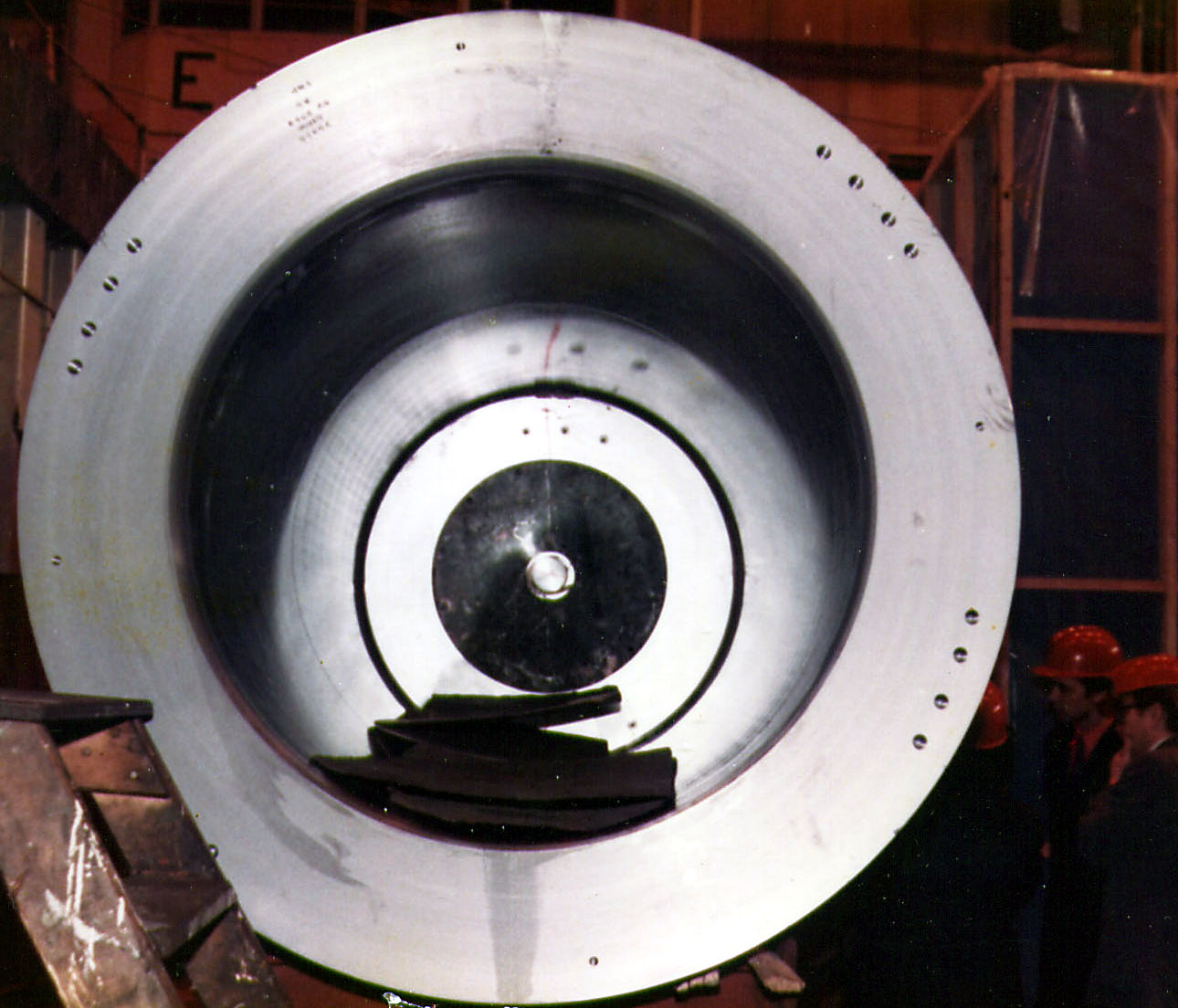

The law is the law! But common sense is common sense! The two pieces of steel was of no value to the user but made up the math that allowed the buying agents to collect their fee. Installation of these simple steel plates in the cylinder would have made them cold presses that also would have not required a license. The attached photograph is the forged cylinder of the press and you can see the bottom with a plug in the center for connecting power. Cold Bottoms were a simple machined steel plate that any large machine in the world could produce for about 30 cents per pound.

The DTI approved the Calcarb sale after a full review. This covered the same materials that were in the seized container but in another form.

From Department of Trade and Industry

To Consarc

Dear Mr. Wilson

SPARE PARTS AND COMPONENTS FOR USSR; CONTRACT NO 50-0166/53467

You wrote to Mr. Hall on 30 August 1985, and followed up with a telefax to me on 10 October 1985, about a contract your sister company Calcarb Ltd. had secured with Machinoimport to supply spare parts as detailed in the annex to your letter to Mr. Hall.

Having examined the details I can confirm your assumption that the items listed are not embargoed and that therefore no export license is required.

Yours sincerely

M B Moore

The items that finally remained as embargoed were obsolete parts made for tests that did not work. They should never have been part of the insurance claim. If Customs had not seized the last container and destroyed it, all the items would have been allowed. My first thought was to fight them on the remaining items, but this was not necessary to settle the contract. We boxed the items in a strong box with clearly marked, "Embargoed items, Do not export."

Machinoimport owed BEPA about twenty three thousand dollars. They would not pay if the company was in default of its contract. Ivanov saw no reason to cancel my contract until he was shown clear documents stating that the contract could not continue using British subjects. He had to obtain his money from the end user, but it was still tied up because Consarc could not get a license for the "cold bottoms."

On the 17th of October 1985 letters were written to all BEPA sub-suppliers informing them that their services would no longer be required due to the recent change in the regulations. Tom Dick continued as consultant to Consarc on a furnace to heat a nuclear related product for the atomic group in the U.K. He departed to Moscow one day later to close the BEPA contract. I agreed that this trip would be paid by BEPA provided Ivanov paid us. On that date Ivanov called to say that his clients were seriously considering Wilson's quote for a retort furnace.

Roberts sent me a fax message on the 21st of October 1985 with a copy to Rowan.

Subject: H.M. Rowan Letter of October 4, 1985

I me with Hank Rowan today to discuss Jim Metcalf's request for a clarification on whether we should proceed with the separate order of Calcarb, Ltd. for Calcarb insulation and spare components, such as mechanical pumps and instruments.

Mr. Rowan and I agree that we should proceed to ship this material since we have the UK Government approval to ship this material, it is a separate contract and does not involve the supply of personnel to which there have been government objections.

Please be sure we have a clear restatement of the UK Government's agreement to ship these items before making the shipment.

R. J. Roberts

During the month of October 1985 the difference between the US and British position on Taiwan became clear. At first the DTI refused to issue a license to export a vacuum melting furnace to Taiwan but when it became clear the US would get the business they changed their mind.

Several telex exchanges between Wilson and Ivanov to settle the cold bottom are in the files as the DTI changed the export rules in Consarc's favor.

On October 30th 1985 I wrote a letter to Dick contained additional instructions. This was after a Consarc Scotland management meeting that Dick attended. Crawford and Cooke were in control and let Dick know in no uncertain terms that he had no right to build a retort furnace for Machinoimport. This situation caused Dick to go it alone and obtain all the future business from the embargoed client for his company, Vacuatherm.

http://www.ioa.com/~zero/531-DickLetter.html

It took the DTI almost a month to compose a letter that told us to stop the contract. But they really could not, and did not, tell us to stop.

From Department of Trade and Industry

To Consarc

Date 1 November 1985

Dear Mr. Cooke

RE: MACHINOIMPORT CONTRACT.

Please refer to our recent discussions and your telefax of 7 October concerning the above contract that relates to the construction of a plant in the Soviet Union. As you know, certain equipment (vacuum induction furnaces and isopresses) which your company was to supply under this contract were made subject to U. K. export control regulations on 8 February 1985. I was therefore deeply concerned to learn of your company's intention to arrange (through, I understand, BEPA) for assistance to be made available for the purpose of bringing the above plant into commission, using the equipment supplied before the imposition of export controls. As I advised you, it is the view of HM Government that the considerations of national security which led us to impose export control on the above equipment continue to apply and would be prejudiced by the commissioning of this plant. I was grateful for your confirmation that your company intends to play no part in action to commission the plant.

Hall

Modern office equipment allows many things. The first step was to make a good Xerox copy of Hall's letter. The second step was to use white ink to remove the final sentence of his letter. The third step was to make a good Xerox of the corrected copy. The fourth step was to send a fax to Hall of the copy with my handwritten note that the above letter was all I needed to show the Russians that BEPA must quit.

Consarc was getting ready to invite another group of Russians to Bellshill to inspect a furnace that I felt was at least as important as the embargoed one. The DTI had answered our requests for confirmation that it was allowed. I wrote them a letter suggesting that they come for a complete inspection before the Russians came to see for themselves that it was still allowed. Rowan told me in a short fax that my method of handling this situation was quite good.

This vacuum melting contract for the Soviet customer required that final tests be carried out in our factory on the fully assembled item. We would not be required to go to their factory. This meant they were doing something they did not want us to see. Tests included melting of superalloy for another sales demonstration and stainless for the Russian customers. Technical data laws are so strict on the old superalloy technology that I did not dare to assist in the tests in front of any foreigners. The Russian metallurgist finally helped our people through the melting tests.

The Soviet customer lived next door to us for two months. Vera and I entertained them, but I did not dare become involved with the test program. We had no one for the metallurgical supervision so the Russians did it themselves. Any order that is not supervised in the field must be suspect. The British gave approval for this job on four separate occasions. In my mind this was more important equipment than the embargoed furnaces.

The Soviet Trade group told me of massive changes in their buying structure. No one knew just what would happen. The London station was very good duty for them. A large group of their fellow workers had been deported earlier that month by the British as spies.

Vera was issued a permit to stay in the U.K. until September25, 1987, in line with my work permit. The immigration officers that interviewed us warned her that she was staying as my dependent only. If I left the U.K. she could not remain.

I visited London on November 13, 1985 to meet with SIGRI, a German carbon producer, and the USSR Trade group. I told SIGRI that our insulation was not yet ready for the market. They had a request to supply the missing insulation to the embargoed Soviet project. There was no law against it, but we were not technically capable of supplying the product at that time. They were very interested in the densified product I had obtained.

The DTI finally responded to my request for a letter ordering us to quit on November 19. "We have carefully considered your request to amend our letter. But the Department is unable to accede to your request. My letter of November was carefully considered and is as far as the Department is able to go."

Consarc sent me to Moscow on November 22, 1985. My purpose was to give a talk on Plansee equipment. Roberts had originally arranged to do this task but ducked out due to the changing situation. I helped Wilson modify the Calcarb contract to replace the cold bottoms on November 25th 1985. The final shipment was scheduled for the first quarter of 1986.

Ivanov said he no longer needed me because he had his supplier. He said he still felt my presence behind a new supplier. I told him I was no longer involved with the project in any way.

BEPA was dormant but the final check had not arrived. I needed this check to pay the bills, and one of the bills was my considerable expenses. Consarc UK had paid for the big ticket items like airline tickets, but there was still meals, taxis and the like that came out of my pocket. I was almost three years behind on my expense accounts. I had a box full of receipts in pound, yen, franc, mark, lira, ruble, and some that I could not remember. Another box was full of every type of small coin. My travel journals were very accurate, but not yet matched to the receipts. I had truly been so busy that there was no time to do this accounting. I asked Cooke to help me but he refused.

Cooke suggested I use an accountant from the company's audit firm. It was a nightmare and it took six days to sort out. It took several months and a board of director's directive before I got the cash. The big hang up was Vera's travel and how to value the Russian ruble she had given me and the Consarc staff. One of the big items was the celebration dinner she paid for when we signed the Russian contract. Vera had the hammer. She was the treasurer of BEPA and could pay herself before paying Consarc when the check came from Ivanov.

BEPA was paid its invoices less the amount for the hotels that Ivanov could not pay. After paying Dick and Consarc, my net loss was a little more than fifty dollars. The cost of setting up the company and of reporting to the government came out of my pocket.

I arranged my affairs for a long trip to Korea. Vera was not able to freely return to the United Kingdom so we had to obtain a return visa valid for three months. A Russian passport was a pain in the neck.

http://www.ioa.com/~zero/532-Korea.html

After the start up in Korea was finished we went to Japan. We departed Tokyo for Los Angeles on January 17, 1886 with a stop in Hawaii. Vera did not like the place I picked because it was one block away from the ocean and had a waterbed. Worst of all, it had a kitchen so she had to cook. This was Vera's second visit and she still did not like the place.

I needed to be in Bellshill for some business, but Vera wanted to stay in Los Angeles to visit with Russian friends. I made a quick trip to Scotland to pay bills and settle other affairs. Scotland had nothing for me to do because they did not like the rate Rancocas was charging. I tried to convince the Scots to push hard on their carbon project to cut costs and start other projects such as CVD. They were building a new welding area to replace one they did not need, and the place was a big mud hole. Roberts wanted me to return to the States.

When I returned I found that Vera's friends had stood her up. She was very angry at the situation. She was staying at a very good hotel near the beach and was able to enjoy herself. We decided to take a holiday in Mexico in late January 1986. Vera traded the fur coat she bought in Korea for two weeks of time share. I bargained six more weeks for dollars, because at that time the Mexican peso was in big trouble. The Space Shuttle, Challenger, exploded at 11:40 AM on the 28th of January 1986 just 72 seconds into flight. I was sitting at the bar drinking a cup of coffee as I watched the horror of the event.

Dick was not able to close the BEPA contract until February. The final agreement to close the BEPA contract contained a provision to pay Dick the rubles for the hotel and some five thousand dollars for his services after the Rowan order to stop. That was the end of the carbon-carbon caper for Ivanov and me.

FROM: Department of Trade and Industry

27 January 1986

TO: T R Dick Esq.

BEPA Ltd.

Dear Mr. Dick

My predecessor, Mr. David Hall, wrote to you last November in your capacity as a director of BEPA Ltd. and of Vacuatherm Designs Ltd. about your intentions in relation to the installation and commissioning in the USSR of plant and machinery supplied by Consarc Engineering Ltd. to Machinoimport.

You discussed the situation with Mr. Hall here in the Department on 12 November and, I believe, were to visit the USSR again shortly afterwards.

As some months have passed, I should welcome an early opportunity to discuss with you how matters now stand. If you are ready to agree to such a meeting I should be glad if you could telephone me so that we can fix a convenient time.

E W Beston

Dick maintained very close contacts with the British authorities. They probably were not pleased with what he was doing but he appeared to stay within the law. I did not attempt to understand or know what he was doing. My contacts with him were strictly social, while he was becoming a wealthy man. Vera has never understood why I lost that position.

Using our time share that we had just purchased on Mexico we lived in Atlantic City for eight weeks. The weather was not good in late March and April, but for Vera and her invited Russian girlfriend it was just fine. They could visit the casinos when the sun was not shining.

I left the ladies at the beach and flew to Japan to help with the selling of a vacuum melting furnace, but in the end it was lost to the German competitor. I had lost my desire to win. I sent flowers to Vera for her birthday on May 18, 1986 from Japan and they were delivered on the beach.

The FBI interviewed me for three days during that visit. It was easy to see that the agent was being debriefed after each session with me. He would arrive at the next session with questions that came from an expert, based upon my answers of the previous meeting. They also interviewed Soderstrom and others with whom I had business contacts on the subject of carbon. The FBI agent agreed to allow me to proofread his report before he made it final so we could correct any errors. In the end he refused to allow me to read the report.

We returned to Scotland where I was resolved to put some life in the carbon insulating company. The management was still dragging their feet on moving the old blacksmith operation out of the building. I arranged to shift the bookkeeping method so as to use the grants in reserve to offset operating costs. This made the losses look smaller. A great deal of material was being drained down the sewer and a large part of the material was being scrapped.

Consarc and Calcarb made their last shipments to the embargoed project in the spring of that year. There was no doubt that all the carbon insulation shipped would crack when used. These shipments were in settlement of the contract and carried no warranty.

Vacuatherm had established itself as Consarc's replacement in Moscow. They had several engineers at the site, including previous employees of Consarc. Dick picked up spare part orders that would have been Consarc's. Inductotherm refused to sell Vacuatherm some parts that were not embargoed. They later agreed to sell them when I pointed out that this act would put all of our companies in a bad light.

The Soviets went to the open market to buy the insulation that was seized at Hull. A Germany company contacted Calcarb for a bid on the material. The DTI finally stated that if the shape was for a 2000 degree furnace they would not permit it. Vacuatherm asked Calcarb for an offer to supply insulation in block form. Wilson wrote the DTI, who finally confirmed that this block material would be allowed. It is my understanding that Dick became angry with Calcarb's delayed answer and may have placed an order with the Scottish based subsidiary of FMI in a perfectly legal transaction. Dick probably reported this fact to the DTI.

Vera and I had the duty of entertaining the final group of Soviet inspectors on the company's last contract with the Russians. This equipment was for hard coatings on cutting tools. The project was almost one year late and the costs exceeded the selling price by a large margin. The Scottish group could no longer justify the apartment where they had housed the previous groups. I sold my apartment as I promised to the British tax people. I used part of the proceeds of that sale to purchase the company's apartment. I had a new address and a new tax situation.

I visited the Soviet Union two times in 1986 in an attempt to find some new business. These trips were primarily to escape the boredom of my job. Gorbachev had put the brakes on spending and was breaking up the buying houses. Most people in Moscow were liking what they saw but did not like the long lines to buy vodka. Gorbachev was a non drinker and was trying without success to stop the Russians from drinking.

My only remaining obligations were to teach the Japanese how to use my new gas shroud process and to teach the Taiwanese how to melt superalloy. Our government had issued licenses for both tasks.

My plan to build a very cheap furnace for the densification of carbon using methane for the Calcarb operation was not completed. The staff in Scotland did not want it and Rowan was blocking my attempt to get into the carbon densification business because I'd be competing with his customers.

Consarc wrote the DTI a series of tongue in cheek letters asking for permission to sell Vacuatherm and other firms insulation for the embargoed project. On October 4, 1986 they notified Consarc that the material in raw form was permissible if it was not the shape of the embargoed furnaces. This letter told Consarc to be aware that changes were coming.

On September 10, 1986 a meeting was held in Washington at the IDA, Institute for Defense Analysis where rigid carbon insulation was discussed using, a classified document that probably was addressed to CoCom members.

The DTI ruled that carbon insulation was a fine ceramic and could not be exported without permission. We countered that ruling with a letter, which in effect made their technical people look like idiots. Calcarb was not going to supply its insulation to the embargoed project in any case, because they felt this would be a slap in the face of their government.

On November 14, 1986 the British government defined the material as a fine ceramic by law. It appears that they did this to block the FMI shipment from their shores, even though it was made in America. Dick may have purchased FMI product through a neutral country to supply the Soviet project.

It took the American regulators a little longer, but under the CoCom agreement they also ruled that this simple insulation was to be regulated. There is no doubt that the information from Consarc Scotland was furnished to the US intelligence people and this was what made them put a spotlight on FMI. The British gave Calcarb an open license to ship the material to any customer with the exception of Warsaw Pact nations. US regulators did not do this for FMI so they had to obtain a license to ship this material.

Dick obtained an order for a five-inch isopress from the Russians that he shipped during this time period. There is no record in my files or in the press that FMI ever discussed the export of their five-inch isopress to India with Dick. Too many events and possibilities exist to rule it out.

Early in 1987 I decided to really concentrate on getting Calcarb out of trouble and on its feet. The Scots had finally moved their old blacksmith equipment out of the carbon production bay. We were shooting ourselves in the foot and without the Soviet contract driving the company the future appeared hopeless. The scrap pile of Calcarb was growing larger by the month. We were burning and dumping down the drain more than eight percent of the material. I discovered that the cracking problem was caused because we let the material lie around and pick up water between low and high firing steps. Starch or resin used to bond the little fibers together was not fully carbonized at the temperature we were using for the low firing step. This unfired carbon reacted with water causing cracking at the next step.

It was time for me to go but Vera did not want to move to America. I decided to stay in Scotland until the Russian and Taiwanese equipment was ready for startup. I also had to complete a $50,000 order to teach a Japanese customer how to use gas purging.

I convinced the Scots it was time to try to get some orders from Russia on my way to Japan to do the IMM project. This trip to Moscow was without any business contacts because none of them had any money to spend. The only contact was with Metallurgimport to take care of a small warranty problem.

In April 1987 my obligations were almost finished. All that remained for me was a job in Japan and Taiwan. http://www.ioa.com/~zero/533-FarEast.html

During the evening flight back to Scotland Vera and I discussed the pending move to Rancocas. The stock market was approaching an all time high so my trust was going to be worth half million and I already had enough money for a lifetime in the banks from the sale of my stock. My bonus was small that year and it did not appear that more than five percent would be paid into the trust. Future projections for bonus and trust payments were slim. If I moved back to the States it would be a battle to displace Roberts. Vera did not want to move to Rancocas so I agreed to try to set up a sales office in London.

On June 19,1987 I wrote the board of directors about my intent to resign as of July 31, 1987. My letter offered to follow through the final protocol for Consarc's last job in Moscow finish the Taiwan task and attempt to close the engineering study with IMM.

Roberts did not call me, but Rowan did. I told him my reasons were personal and that he understood my position on the carbon business. I told him I could not work under Roberts and that it would cause friction if I returned. Rowan asked if I would continue to consult for the vacuum melting side of the business. I agreed to do it under certain conditions.

The furnace job in Moscow was not ready so I went to the next task. Before departure to Japan I informed the British Embassy of plans to set up a business in the UK. Forms were submitted for settlement in the UK. Vera remained in Moscow.

I met with the Japanese customer to discuss the final results of the test program. We signed an agreement so Consarc could be paid. I discussed my resignation with Toru Yamaguchi, the firm's president, and agreed to remain as consultant to Consarc during a design study phase for his upcoming project.

I was in Taiwan for two weeks to finish the melt program. We agreed that the job was finished pending only the results of the forged metal and reprogramming the computer.

I returned to Moscow and arranged for the completion and sign off of Consarc's last Soviet job. I announced my new status to my contacts in the Soviet Union. This final customer was hardening tungsten carbide tools for high speed automatic machines in the automotive industry. This operation was run by a world class metallurgist, and among other metals this factory produced niobium. He told me that the geologist had located a seam of high quality niobium ore in the northern Ural range. He told me there was enough minerals in this one seam to overwhelm Brazil in niobium and South Korea in tungsten.

Vera and I did not report any change in our status when we arrived in London because I was still a director of Consarc and our work visa did not expire until September 22 of that year.

I was resigned my job but there were loose ends to tie up. Reports had to be completed and expenses submitted, so I continued to go to the office at Consarc. I attempted to set up a pricing list for the Japanese market, but Gee, the long awaited technical manager for Calcarb, wanted nothing to do with me. I reminded him that I was still a legal director of his company. I was having very serious thoughts about taking back my letter of resignation. Rowan would have backed me but the local crew wanted Jimmy to disappear. On the 31st of July 1987 notices were posted of my resignation were posted on the bulletin boards.

On the 12th of August 1987 Cooke told me that I had to resign as a director of Consarc and Calcarb. I asked him to allow me to remain in that status until my visa problem was settled. He told me he had orders from Roberts. Cooke wrote a contract for my future 100 day of work. He wanted title to any of my ideas or designs for a simple day's payment. I would not sign it and besides I had no legal right to work in Scotland without a work visa.

I met with Dick twice during that period to arrange some way we could work together. We both agreed that I would stay completely away from the embargoed project he was working on. No doubt he was able to blame me for any mistakes in the project and to take credit for the good things. My reputation with this customer must have been very low. I never saw this project or spoke with any of the people again. Later a newspaper reported that I was selling their product in the UK.

I wrote my Japanese customer (IMM) offering my services as a consultant. This deal was already set up, but IMM was a small division of a large company and it would take time before any income would come from this source.

I wrote a German client offering a joint venture to produce some carbon parts using gas phase densification. I met with this client in late August 1987. I told him I would agree to some kind of joint venture but I would have to obtain a license from the USA that would require documents from his government. He refused to apply for a license and stated he would never consider living in a country that restricted his freedom that much.

I had a chance meeting with Dick in Munich in early September. He invited me to attend a meeting with him at a Germany carbon company where I also had an appointment. They were considering a drawing of the heating element for the hot isopress that had been embargoed. The material itself required a license to be shipped to Russia, but not to a customer in Austria. Such is the stupidity of some trade regulations.

The main reason for the meeting was to discuss material for the elements of a furnace type that could be exported. I could not resist making comments and suggestions to improve the plan Dick offered. Here was another stupidity in the regulations. If a material was regulated but was shaped as a heating element of a furnace that was allowed then it could be shipped without any problem. The final stupidity, and the one that Vera could not understand, was that Dick as a British citizen could take his mind to Moscow and speak and make designs of anything he wanted. I, as an American, could not do that. Vera asked simply: " Where is your freedom of speech?" I agreed but told her, "I don't want to go to jail."

When I returned to London, I told immigrations about my change of status and the pending application to set up a business in the U.K. They gave me a visa for six months that did not allow me to work or engage in any business activity.

On August 28,1987 I registered a change of status to the Motherwell police. Vera received permission from immigration to remain until February 1988, in line with my visa. The officer told me the Home Office had more than one hundred thousand letters they had not yet opened, so he was not surprised that we had no answer on Vera's application to become a British citizen.

I was now in a strange tax position because my visa did not allow me to work in the UK. My tax position in the US was no longer that of an employee on assignment in a foreign country. My income for 1987, plus the requirement to liquidate, or roll over, my trust fund in Consarc that year, left me with a large tax bill. My accountants in the UK were still trying to settle my tax liability in the UK for time worked in their country. Tax laws in the USA allowed me to deduct about eighty thousand dollars if I remained outside the USA for 330 days during any one-year period. I had to walk a tightrope to stay out of any territory of the US (including flying over any territory of the US) that would count as a day in the country.

I flew to Brazil to do some consulting work with a change of airplanes in Miami. The connecting flight did not leave the territory until after midnight. For tax purposes I had used two days.

http://www.ioa.com/~zero/534-Brazil.html

I was in Brazil while Knute Royce from Newsday, a Long Island tabloid, was visiting the UK and France to investigate his carbon-carbon story.